By Allen Cowgill

University of Colorado Denver professor Dr. Wes Marshall started his career as a traffic engineer, but he quickly realized that safety rules in the profession were built on what he described as pillars of sand.

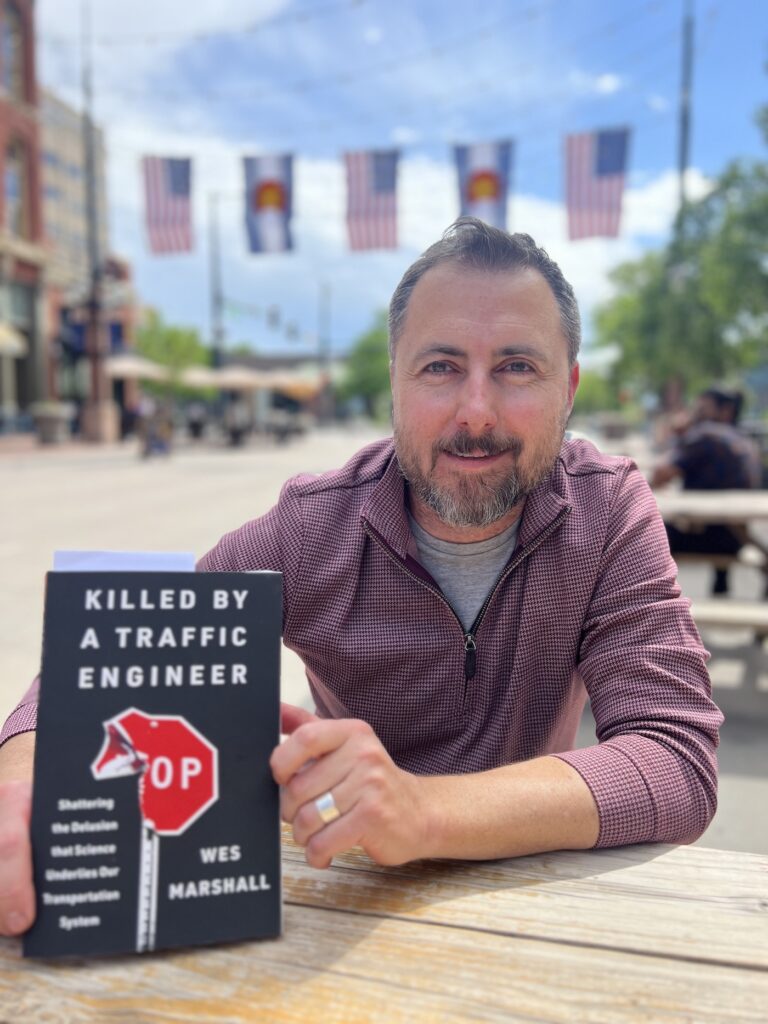

Marshall’s new book, “Killed by a Traffic Engineer,” details the myriad of systemic failures that have led to record numbers of traffic deaths.

Traffic crash deaths have taken the lives of more people in the United States than all U.S. wars combined, said Marshall, who has written more than 70 research papers on streets and transportation. He wanted to use this book to go after the foundations of the system.

“The real problem isn’t just that we put Band-Aids on our problems,” Marshall said, “which is the vicious cycle we are stuck in now. We create terrible roads, throw Band-Aids on here and there, but they don’t fix what led to problems in the first place.”

Marshall’s book opens with a comparison to the very early days of the medical profession, when, one could argue, more people were killed by it than helped. For example, even as recently as the 1940s, Marshall writes, “doctors used X-rays to remove unwanted hair … and gave people cancer.”

The book then pivots to the traffic engineering profession, which is less than 100 years old and has produced a “system that incites bad behaviors and invites crashes.”

Marshall asserts that there isn’t one fundamental problem with the system, but many.

Crash data, for example, focuses on human error such as speeding, driving through red lights or jaywalking. Holding the road user at fault lets traffic engineers off the hook, Marshall said, even when data could have predicted the outcome or better design could have prevented crashes.

“Just to say it’s random user error doesn’t get at the fundamental problem, that the system is creating that error,” Marshall said.

In another example, Marshall describes how engineers often create wide roads – much wider than needed, and designed like highways – that easily allow, even invite, drivers to exceed the speed limit.

He notes that it’s not an error that everyone is speeding on streets like Federal Boulevard, it’s simply typical behavior for the street given its design.

When asked why Federal Boulevard is one of the most dangerous streets in Denver, especially for pedestrians, Marshall pointed to crash statistics that do not address the fundamental problem of the street. For example, if someone jaywalks and gets hurt or killed, the police will often cite jaywalking as the cause of the crash.

“As engineers and planners, we look at that data and we don’t think we did anything wrong, we just look at it and think we need to put more money into education and enforcement,” Marshall said.

Marshall advised that we take a step back and try to understand why a person would illegally cross the street. The person may have jaywalked on a street like Federal because the nearest crosswalk is a half-mile away and sidewalks leading there might be nonexistent or impassable. He said that road users don’t want to get hurt, but that the built environment and road infrastructure can lead them to make decisions that seem rational given their options.

“To me, that is our fault as engineers that we are not providing people with a safe place to cross,” Marshall said, “but the data would never tell us that. I think we need to dig deeper.”

Marshall noted that the streets traffic engineers have spent the most energy re-engineering, widening and building for speed, like Federal Boulevard, are often the most deadly. Whereas neighborhood streets that have been minimally altered or remain unaltered by traffic engineers are often the most safe.

Marshall also described rules of the profession that are not grounded in safety. For example, many traffic engineers will set a steet’s speed limit based on what they call the “85th percentile rule.” This is the speed at or below which 85 percent of drivers travel on a road segment. So instead of basing the speed limit on what may be the safest for the road conditions or the community the road goes through, it bases the speed limit on how fast drivers are able to travel down the road.

Marshall noted that among the most significant of systemic problems are engineering schools that teach traffic engineering practices that lead to systemic failures.

Marshall said it gives him hope that CU Denver is trying to provide forward-thinking tools to traffic engineers and planners of the future. A new university program, Human Centered Transportation Education, will offer a minor, certificate, dual-degree and graduate-level programs.

Allen Cowgill is the City Council District 1 appointee to the DOTI Advisory Board, where he serves as the board co-chair.

Be the first to comment