By Mary Lou Egan

In “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” the award-winning, 1956 film biography of boxer Rocky Graziano, middleweight boxer Ruben “Cowboy” Shank is mentioned. Shank would receive a royalty for the use of his name, and in his later years he would really appreciate this money.

Born in 1921, Shank was one of eight children in a family of German Russians who emigrated in 1913 and worked on farms in LaSalle, Keenesburg, Fort Morgan and Brush. All the sons, Emil, Fred, Adam and Ruben, helped with the farm. They also trapped coyotes, muskrats, beavers and raccoons. Boxing provided another means for the boys to supplement the family income.

There were plenty of opportunities to pick up boxing experience in high school “smokers,” and there were cash prizes to be won at county fairs, rodeos and Elk’s clubs.

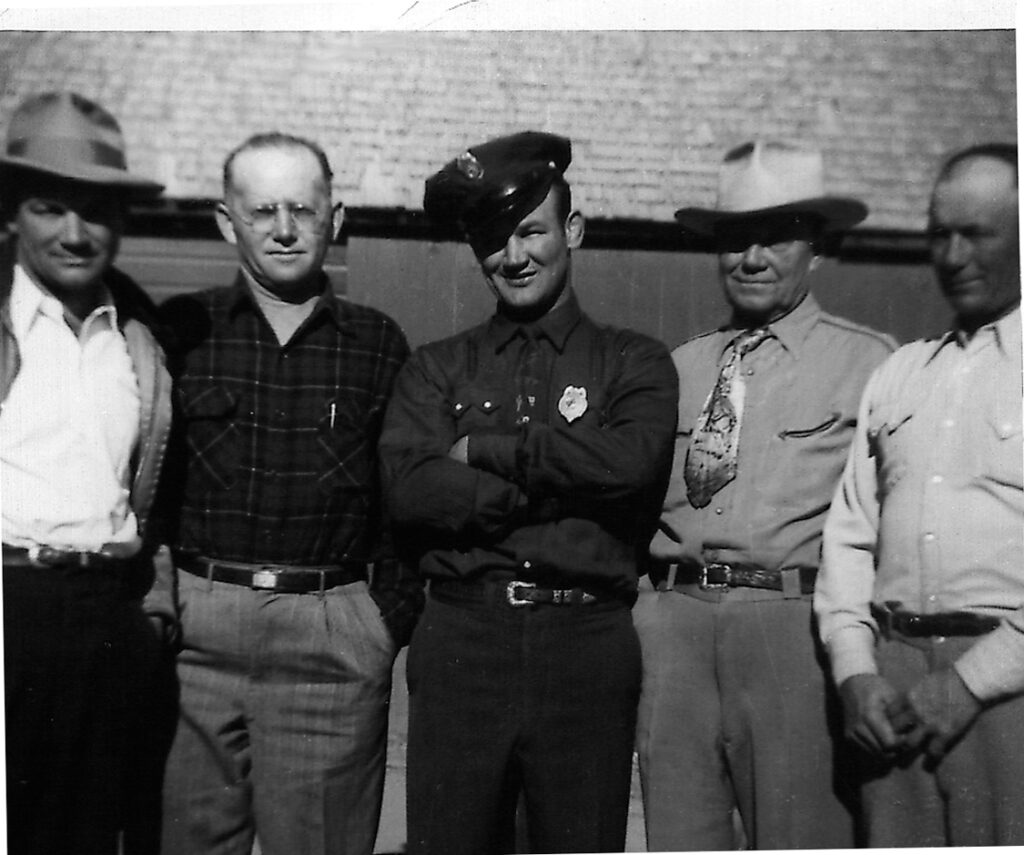

After Pearl Harbor, Adam Shank enlisted in the Army and Ruben Shank in the Coast Guard, where the brothers continued their boxing careers. The military promoted the sport, arranging matches and providing coaches, training and gloves. Victors were awarded war bonds. Nicknames like “One Punch” Adam, and “Cowboy” Ruben Shank were an important part of publicity.

In a 1997 interview, Ruben’s niece Betty Reed explained, “After a lot of the fights Ruben won, he was given a silk cowboy shirt. In Madison Square Garden they heard about this ‘Cowboy.’ You know, they thought it was all cowboys and Indians out here, and they were kind of making fun of him. His manager was a guy named George Knorr, and he just ran with it.”

Ruben surprised the boxing world on April 23, 1942, when he easily won a match with Fritzie Zivic, a brawler who was noted for “thumbing” the eyes of his opponents. A July 3, 1942, victory over triple-crown titleholder Henry Armstrong at the Denver Auditorium was much closer, causing some critics to complain of hometown bias.

Shank’s continued success over former champions catapulted the 20-year-old newcomer to a bout with Sugar Ray Robinson in Madison Square Garden on August 22, 1942, one of the most important competitions in Shank’s career.

The underdog Shank started fast, pummeling Robinson. But Robinson came back in Round 2 to drop his opponent four times and finish him. For several years, the scrappy Globeville resident continued to challenge big-name competitors, losing twice to former middleweight champ Fred Apostoli in 1946.

It was a match with Melvin Brown in Minneapolis that resulted in Shank’s knockout loss and damage so severe that he nearly lost his life. Although he slowly recovered, the National Boxing Association ruled that Shank couldn’t fight again and his then-manager, Chris Dundee, agreed.

In 1952, Shank challenged the decree in Denver District Court, and Judge Henry Lindsley ruled that the boxer could resume his career. Armed with the ruling, 31-year-old Shank fought a dozen more times, possibly contributing to his difficulty speaking as he grew older.

For 28 years, Shank worked for the Denver Public Works Department and moonlighted at the Mile High Kennel Club.

In December 1995, Ruben Shank passed away at age 74. Friend and former boxer Ray Schoeninger remembered, “Ruben was the nicest and most honest person you’d ever want to meet. I was with him at the Stock Show once when Ruben found a bag with thousands of dollars inside. He chased the guy down and returned the money. He was very good to people.”

Mary Lou Egan drew from the following sources for this month’s column:

“Ex-boxer Shank Dies at 74,” Denver Post, December 14, 1995, by Alan Katz.

Interview with Betty Reed and Carol Christensen, Wheat Ridge, Colorado,

February 16, 1997.

Mary Lou Egan is a fourth-generation Coloradan who loves history. You can reach her at maryloudesign@comcast.net.

Be the first to comment